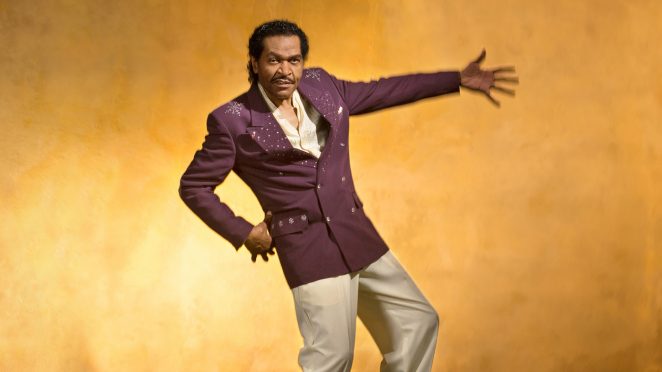

“If you don’t like the blues, you probably don’t like your mama,” states Bobby Rush, the passionate blues legend who turns 85 in November. Rush is blues music royalty, a rare breed that can count iconic names like Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and BB King as not only artists he’s performed with but friends that became part of his colourful life. He’s recorded close to 400 songs and in 2017 was finally bestowed with the recognition he’s so long deserved, a Grammy Award for Best Traditional Blues Album for his 2016 record Porcupine Meat. Australian fans will soon get the opportunity to witness this true blues legend in concert when he appears at Bluesfest in Byron Bay (29 March – 2 April). Australian Musician’s Greg Phillips had a chat with the amiable Rush ahead of his Australian trip.

Bobby Rush is known by his peers as King of the Chitlin’ Circuit. In the 50’s when Rush first began performing he played gigs in America’s south, being paid in chitlins (prepared food usually made from the small intestines of a pig). “The chitlin circuit was where you played for food,” explains Rush. “They’d feed you chitlins. Sometimes we’d play so well, they would give me two plates and I would sell one and eat the other, so I’d make an extra 50 cents. At that time we were only making 50 cents a night back in 1951.”

Not only were the black performers of the day paid very little but unbelievably sometimes had to sing from behind a curtain. “Oh God yeah, in the early 50s I’d play behind a curtain to a white audience,“ Bobby tells me. “They wanted to hear my music but they didn’t want to see my face. I’m one of the few artists that had the chitlin circuit audience but now also have the crossover audience. But I have to be careful, I want to cross over but I don’t want to cross out my people. That’s important to me.”

Despite the hardships of being a black performer in 50s America, Rush was determined to make a name for himself and really knew nothing else but the blues. His first crudely-made guitar was constructed with a broomstick and a bottle. “I got a broom and I put some wire on it,” Bobby says. “You put a bridge at the top and a bottle at the bottom. Then I reversed it and put the bottle at the top. One day the bottle fell off and hit me in the head! I got through those days by trials and tribulations and just wanting to do it. I wanted it so bad that nothin’ could deter me. Nothin could discourage me. All the ups and downs, nothin’ could turn me around. Rain or shine I was going to be a blues guy and I knew that when I was seven years old. I didn’t know it was going to turn out this way but I knew what I wanted to do.”

Rush doesn’t have many regrets in life but he does wish he’d hung on to a song called Hoochie Coochie Man, which was offered to him by Willie Dixon. “It was called Hoochie Man then,” Bobby recalls. “He didn’t have the song completed when he came to me with it. I told him it was too old for me and to give it to Muddy Waters … like a crazy man!”

Years of persistence finally began to pay off for Rush but he always remained humble and when he did start to make some money, his first purchase was more practical than extravagant. “I did buy me another guitar man but I bought one this time with a case!” he says. “Most of the time I had a guitar without a case. I’d been carrying my guitar wrapped up in a cloth. When I bought a guitar with a case I was in heaven. It wasn’t a cadillac car, it was a guitar. I bought the guitar from a pawn shop and the case from a guitar shop. God, it took a long time for that man. I still have that guitar but not the case.”

Bobby has always had his tongue firmly entrenched in his cheek with his music, particularly in regard to song titles. His first gold record was for the quirkily named Chicken Heads. His Grammy Award winning album was titled Porcupine Meat. “It comes from bein’ in love with someone and you know they don’t love you,” he tells me as he begins to explain the song’s origins. “You want to leave but you don’t want to leave. You’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t. You know you should go but you can’t. Your mind says go but your heart says stay, so that’s porcupine meat! It’s too fat to eat and too lean to throw away. You know, if I leave this girl I might get someone just as bad or worse.”

The Grammy Award which followed for Porcupine Meat was an accolade he thought would never arrive but he’s grateful it did.

“Oh God, it was important,” he says. “Somebody said you’re late gettin’ it but it’s better late than never. I was up for a blues award 31 times and I think I won 18 out of 31. I was up for four Grammy awards and I won 1 out of 4. I’m on a high man… I had no idea that I’d become some kind of superstar. I didn’t think anybody would ever notice me. I thought I was just going to be a guy who had fun playin’ the blues… I accepted the award on behalf of so many guys who didn’t get the award that came along before I did.”

The world around Rush may have changed dramatically since playing the chitlin circuit but his principals and his attitude toward making music hasn’t changed at all. “I write when I am alone, by myself with no company and listen to myself and some old records,” he tells me. “I write from life experiences and where I wish I was and what I wish I could be and what I thought I might be if I didn’t do music. I write about life and hope.”

Rush is grateful for much in life but most of all he’s thankful to his family and parents for the freedom they gave him to be himself.

“I’m most proud of my kids who understood and let me do what I do for a living,” he says. “Most people don’t let you do what you feel to do. If I had failed I don’t know what they would have thought of me. There was a time when I wasn’t doing as good as I’m doing now and I don’t know what they thought of me. I am so proud that my family didn’t give up on me. I guess I am also proud that people accept me for who I am and what I am and for what I do. My mother and father never talked to me about blues being the devil’s music. They never come to see my show but they never put me down for what I was doing. My father never told me to sing the blues but he never told me not to. My daddy was a preacher, so if he had said don’t sing the blues, I probably wouldn’t have but he didn’t. I have so much respect for him.”