JEFF BECK – CLASSIC 70’S INTERVIEW

November 21, 2005 | Author: Steven Rosen

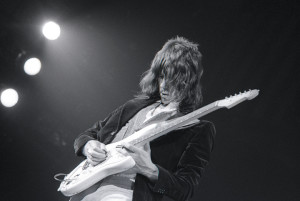

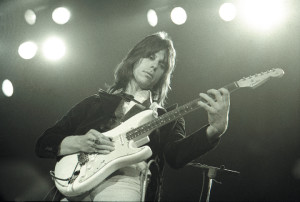

Jimmy Page once remarked about him that he “Plays guitar like he drives his cars,” recklessly, dangerously. So when Geoffrey Arnold came into the world on that war-shattered summer’s day in 1944, he probably felt right at home amidst the hellish race being run by warring nations, feet stomping mercilessly on the accelerators of tanks and armoured cars, and the notion that coming in second meant you didn’t come in at all. On June 24th of that year, in Wallington, Surrey, Jeff, on some pre-cognisant level, may have sensed the bombs dropping, the terrified screams of family and friends, and been aware that he had been delivered into a place of turmoil amidst the exigencies of a world gone whack. Not in any percipient way, of course, but emotionally, in the way the mother tries to protect the child from all things evil, in the way she cradles her baby to keep him from harm. Who can really say how much of these early years Beck could remember but certainly, later, his playing would resonate with a sense of mournful urgency, his guitar a weapon capable of bringing people to their knees, of subduing entire audiences with a single soul-shattering note. As if, through the ululation of his guitar, with the lugubrious lines he played, he was trying to erase something, to forget something. Or maybe trying to give electric expression to those tenebrous and murky memories floating somewhere in his past.

Jimmy Page once remarked about him that he “Plays guitar like he drives his cars,” recklessly, dangerously. So when Geoffrey Arnold came into the world on that war-shattered summer’s day in 1944, he probably felt right at home amidst the hellish race being run by warring nations, feet stomping mercilessly on the accelerators of tanks and armoured cars, and the notion that coming in second meant you didn’t come in at all. On June 24th of that year, in Wallington, Surrey, Jeff, on some pre-cognisant level, may have sensed the bombs dropping, the terrified screams of family and friends, and been aware that he had been delivered into a place of turmoil amidst the exigencies of a world gone whack. Not in any percipient way, of course, but emotionally, in the way the mother tries to protect the child from all things evil, in the way she cradles her baby to keep him from harm. Who can really say how much of these early years Beck could remember but certainly, later, his playing would resonate with a sense of mournful urgency, his guitar a weapon capable of bringing people to their knees, of subduing entire audiences with a single soul-shattering note. As if, through the ululation of his guitar, with the lugubrious lines he played, he was trying to erase something, to forget something. Or maybe trying to give electric expression to those tenebrous and murky memories floating somewhere in his past.

As a teen he was transfixed by the sounds emanating from the guitars of Scotty Moore, Cliff Gallup, and Johnny Meeks. As the guitarists for Elvis Presley (and later Ricky Nelson) and Gene Vincent (Meeks replaced Gallup in Vincent’s Blue Caps) respectively, they would propel Beck into the electric and frenzied atmosphere of the guitar, a stringed instrument that immediately spoke to him.

The list of people that I love is so long, that I couldn’t even begin to tell you. It’s just my whole background. The first thing that changed me was hearing Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent and Buddy Holly, those guys. I never even was considering being a musician. I just had the balls to pick up a guitar and try and play. Then when one of my schoolmates heard me play ‘That’ll Be The Day’ and then he told everybody at school, ‘This guy can play ‘That’ll Be The Day’ and I had to play it. And that’s how I started; that lead break was like a honky tonk piano but on guitar. That’s what they loved about it because it was kind of perverse. Anybody could sit at a piano and play like that but it wasn’t the same. The magic is the string instrument making that sound. I know every lick he ever played; I’ve played all of them.

Jeff began the journey, tracking down these sounds, cataloguing them, making sense of them, giving them shape and substance inside his own head. Finally, the irresistible urge to cradle an instrument in his own hands, to caress the strings and fondle the smooth and refulgent veneer, overwhelmed him. Like a hunter in search of prey, Beck’s senses were heightened as he set out to stalk the great woody mammoth. The thrill of the chase culminated in the lair of a childhood buddy.

“A friend of mine had a guitar, a beaten-up old acoustic thing. It had about one string but that’s all I needed because I couldn’t use any more. One string was plenty for me to grapple with. Then that broke and where were we gonna get another one from? I didn’t know. ”

Not to be denied, he set about building an instrument of his own.

“The first one I made was out of a piece of cigar box and I then progressed on that. Cut the front and back out of plywood and made steamed-round sides, and glued it all together.”

While his father was an avid music devotee, Jeff’s constant plucking and picking pushed and pulled him to the limits. He seemingly supported his son’s endeavours, encouraging him to indulge in music and arts while at school, but this may have been little more than tolerating the noise. Ethel recognised the burgeoning talent streaming from the boy’s fingertips but there was little she could do to stop this inexorable scree that had been building for years. In a landslide of pent up rage, Papa Beck did a dance of destruction all over Jeff’s guitar – and his growing dreams. Demoralised and made to feel insignificant, Jeff knew this was not the end of his dream but the beginning. Looking at the broken pieces of the guitar lying there on the ground must have felt like a slap in the face, and aroused by the visual, he found true purpose and determination.

While his father was an avid music devotee, Jeff’s constant plucking and picking pushed and pulled him to the limits. He seemingly supported his son’s endeavours, encouraging him to indulge in music and arts while at school, but this may have been little more than tolerating the noise. Ethel recognised the burgeoning talent streaming from the boy’s fingertips but there was little she could do to stop this inexorable scree that had been building for years. In a landslide of pent up rage, Papa Beck did a dance of destruction all over Jeff’s guitar – and his growing dreams. Demoralised and made to feel insignificant, Jeff knew this was not the end of his dream but the beginning. Looking at the broken pieces of the guitar lying there on the ground must have felt like a slap in the face, and aroused by the visual, he found true purpose and determination.

“My old man threw it out in the garden because I had a row with him. He busted it and that was the thing I wanted to do so much. So, I’d go down to the local music shop and wait ‘til the place was pretty packed out and I whipped one of these pickups right out of the shop. It sold for about two pounds, this pickup, which was about six dollars. Oh, boy, I couldn’t have cared if I’d got thrown in jail for six months. I had my pickup and there was a little hole waiting for that pickup for about eight months and it fitted perfectly because I had already got the dimensions from a plan. And it just slipped in there with two screws and boy, I was the king!

“I used to deliberately carry my guitar around without a case so everyone could see what it looked like. I used to ride a bit with it, stick it on my back and ride a bicycle. I could see then it just wasn’t a fly-by-night thing because the expressions on people’s face when they saw this weird guitar … that was something. It wasn’t something boring like a violin or a sax in a very stock-looking case. It was bright yellow with these wires and knobs on it. People just freaked out.”

This response, from friends and strangers alike, buoyed the young man’s self image. His devotion to the instrument, this attraction to and awe of the sounds the strings created, and the important sense of stature and self-confidence instilled in him by the very idea of the guitar, pushed him on the road in achieving greater musical realisation. The guitar became an anodyne, a tool that both calmed and comforted him, and at the same time, energised him. If, at home, his hunger to hear words of encouragement was never satisfied, all he needed to fill the yearning was a strum and a hastily phrased solo. Prodded by his own common sense, and maybe gentle parental guidance, he sought out someone possessed of a greater knowledge, a more encompassing musical vision. A teacher. That grand mentor who, with the benefit of years of playing and accumulated wisdom, would inculcate within him all the secrets the fretboard had to offer. Alas, the quest yielded nothing but a wasted afternoon.

“I went for one lesson on a Spanish guitar but not the one my friend loaned me. Because there were rumours going around my school that you couldn’t’ possibly play any guitar, any electric guitar, unless you had proper classical training. I was a bit thick then and I said, ‘Right, okay, where do we start?’ And I went straight up to the guy who gave lessons and he knew less than I did. I said, ‘Now listen here, if I’m gonna get on I just better leave and go home,’ because he didn’t even have the barre chords right. I’d read up before my first lesson and I learned a few shapes and stuff and I was expecting this man to teach me everything in a couple of minutes.

“And he said, ‘Right, now practice this, no playing, just practice putting your finger across the neck.’ And I went like that [laying the digit across the neck] and I said, ‘Right, where do we go now?’ He said, ‘Well, that’s it, I want you to go home and practice that for a week.’ And I said, ‘Well, I at least want to hit the strings once.’ No way.”

Jeff, still a rebel without applause, sought out like-minded schoolmates and began playing in amateur outfits around the area. He landed his first paying gig at a local fairground where he “Boogied around playing Eddie Cochran stuff.” Though he was beginning to create a name for himself, including the lead guitarist position in the Bandits, an instrumental band relegated to supporting Gene Vincent-molded vocalists during a tour then crisscrossing Britain, upon graduating school he was confronted with a Big Decision – keep pursuing music or venture into art college. Still uncertain about the real life possibilities of generating a livelihood as a musician, a confused Beck entered the Wimbledon School of Art for a two-year fine arts course.

As it turned out, art schools provided breeding grounds for musicians in flux. One of the more important connections Beck made was when he joined the Deltones, sharpening his skills as a player and finding himself in the studio and recording a track called “Wedding Bells.” There was fiddling about with other swiftly dissolved pick-up groups and though he was advancing his career, albeit in short steps, income was all but non-existent. Grunt work as a painter, carpenter, driving a golf course tractor, milkman, and road sweeper provided miniscule amounts of spending money but only resulted in fragmenting his focus even further.

In 1963, he landed his first gig with a band showing some real promise. The Tridents represented an early showcase for the transcendent, multi-textured guitar sounds Beck would become famous for in later years. The group cut several sides, raw recordings undertaken in an attempt to lure promoters and hence, more high-profile engagements. Even at this early date, the young English picker was experimenting with sound-shifters including fuzz boxes and a German-built echo box made by Klempt. This Echolette included delays and Beck, already under the influence of Les Paul and his Black Box, began experimenting with the mutating and morphing of sounds.

Making “Lots of vulgar noises on the guitar,” Beck found himself in a no-win situation – he was not particularly pleased with the quality of the music or the substance of his own playing and he reckoned that if anybody took notice of his playing on these various demos, he would be forever mired in a world built on artificial flash and fancy. There was no reason to worry since virtually no one ever heard these performances.

After his early forays into building his own instrument, Jeff fiddled about with various low-rent instruments. Eventually he elevated to a Telecaster and then bought an Esquire from John Maus of the Walker Brothers.

“There was a group called the Walker Brothers [To clarify, the Walkers weren’t brothers. Scott Walker was born Noel Scott Engel and joined vocalist John Maus to form The Dalton Brothers. They added drummer Gary Leeds and became The Walker Brothers]. They came out and they were very sweet looking L.A. kids. One was a real smoothie with his blonde curly hair and his brother [incorrect] used to play drums. There was Scott Engel [nee Walker] and he looked more like a brother than the other kid’s brother than the drummer did.

“So it was John, Scott and Gary Walker [Leeds] and it was John Walker [Maus] who had an Esquire that I really fell in love with. He sold it to me for seventy-five dollars. All the guitar freaks were like, ‘Hey!’ They’d all been putting on the black scratch plate but they didn’t have the blonde neck to go with it. And I had the blonde neck; I was the cat’s whiskers again. I’d been playing this Esquire and just got to grips with it. I gave my other Telecaster to Pagey. He used to play that. He had it painted all psychedelic and it had a sort of a finger plate on it, a scratch plate.”

Jimmy had already established himself as a session whiz kid and had coincidentally attended art college with Annetta Beck (sister). Page was responsible for introducing a still wide-eyed Beck to the music scene and, of course, provided the entrée into the Yardbirds. The pair developed an immediate rapport when realising a common love for players like Scotty Moore and James Burton. They spent some time with each other, trading licks and listening to American blues records.

Around this time, Beck was performing with singer Brian Gibb, an artist working under the pseudonym Johnny Howard. Page was summoned to play on a Howard recording, A Tommie Sands composition called “One Of A Kind.” When he realised Jeff had been working in Johnny’s band, the duo chuckled themselves silly.

“I actually first met Jim through my sister. She went around with a cat at art school who was into guitars and he knew a guy that he wanted me to meet. Because he heard from my sister that I was wild about guitars. And in those days there were not even too many people who knew what electric guitar was. So I went over and met this guy, Barry Matthews, and he was a freak for the guitar even though he couldn’t play it. He made his own guitar. It was dreadful. It had a horn up here somewhere about eight inches, ten inches long ‘cause he was an artist and every thing that he saw was distorted in his own way. He used to just draw pictures of them. He used to draw strip cartoons of rock bands way back in 1965. And he said, ‘Come over and meet Jim,’ and as a matter of fact, I already knew the guy. Not personally but I’d seen him play in a group called Neil Christian and The Crusaders.”

Fate is a strange mother and sometimes gathers her special children and sets them in a playpen separate from the others. Beck had witnessed Page and the Crusaders when they appeared at the same fairgrounds where he was bopping around unleashing those Eddie Cochran riffs. His impression of the young, budding guitarist is classic.

“Pagey was raving around with a big Gretsch Country Gentleman. And it looked big on him because he was a shrimp, even smaller than he is now. And all you saw was this guitar being wielded by a pipe cleaner man. And he had a guy in the group who had an oval bass drum, a Trixson. It was triangular and had to pedals instead of using two bass drums. And I was most impressed with this guy [Page]. He used to play really fiery sort of fast stuff but nobody was listening, nobody wanted to hear him. I was most impressed with this guy. He used to play real fiery. Nobody was listening, they all wanted to hear Bobby Darin and ‘Dream Lover’ and all that. He wasn’t playing funky at all; it was just sort of ‘Hava Nagila’ – terrible but it was impressive.”

Jeff was seeking an identity, seeking out the tools that might best define him. If, to paraphrase Webster, evolution is “change determined by technological factors … a movement from simplicity to complexity, ” then the player was evolving. Sort of. He had graduated from a self-made instrument to a Guyatone, a Burns, and finally an assortment of Fenders; a Natural Selection of amps included a homemade catastrophe, various local brands, and then the metamorphosis-type leap to the Vox and later, the Marshall. The tools became more elaborate, more sophisticated, but not necessarily more manageable.

If Jeff was trying to create an identity, a sound or technique people recognise, the process was working. Pete Townshend took notice. In fact, Pete was going through the same sorts of problems as Jeff – upgrading to more powerful amps and being confronted with the phantoms of feedback.

“I mean there were a lot of brilliant young players around,” the Who’s guitarist recalls. “Beck was around who was even … I think Roger first saw him when he was in a group called The Triads or The Tridents or something. And he came back and he said that there was this incredible young guitar player. And Clapton was around and various other people who could really play. And I started to get quite interested in feedback but I was very frustrated at first. Because I couldn’t do all that flash stuff. And so I just started to get into feedback and expressing myself physically.

Beck, too, turned to violence when necessary. “Feedback was unavoidable because playing in small clubs you always get feedback; bad systems and really the electrical thing hadn’t been sewn up. All the amps were underpowered and screwed up full volume and always whistling. My amp was always whistling. And I’d kick it and bash it and a couple of tubes would break and I was playing largely on an amp with just one output valve still working. It would feed back, so I decided to use it rather than fight it. It was hopeless to try and play a chord because it would just ‘rrrrr’. So then when I progressed on to a bigger amp and I didn’t get it, I kind of missed it. I went to hit a note and there wasn’t any distortion; too clean. It was horrible. So the ideal thing was to get the beauty of the feedback, but controllable feedback.”

In speaking with Jeff, and trying to pry from him the reasons for his various detours, exits, exoduses, and simple petulance, there is no answer forthcoming. He is at a loss to find a reason for some of these actions. Why he smashed The Jeff Beck Group into tiny pieces and divorced what may have been the greatest marriage of singer and guitarist ever recorded in the annals of rock is still impossible to answer. Yes, Rod and Jeff were at each other’s throats, money was apparently disappearing down invisible pockets, but what’s new? Rock is built upon creative accounting and fragile egos. Leaving the Yardbirds at the virtual height of their popularity? Disbanding the Bob Tench-fronted band? Did he have a clear understanding of why he made these decisions?

“No, God no, I had no idea when I started playing it would turn into what it is now. I would have worked my balls off; I would have got it right. I wouldn’t have wasted my time. But who knows? I might be wasting my time doing something now. Something might be passing us both by now. If the press would give me a chance, I might come up with something new. They might not realise it, but I play from emotion. I’ve never consciously tried to be a flash. Emotion rules everything I do.

“I don’t like to try and baffle people. If chicks are gonna stand there and look at each other then I’m wasting my time. I want to play notes and stuff and chord construction that they understand. If you’re gonna hit a chord with heavy discord, it may be painful for somebody to listen to. So, I’ve tried to kind of incorporate dazzling playing and at the same time make it commercial.”