JOHN BUTLER- GRAND NATIONAL

March 16, 2007 | Author: Greg Phillips

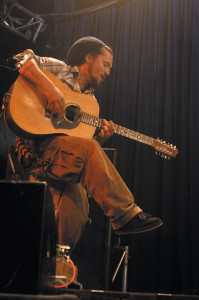

The man greeting us at the door of a swish modern suite in a flash Melbourne apartment block is John Butler. There’s something odd about the sight of Butler in this environment, in the same sense you’d ponder a man wearing a suit in the wilderness. There’s no reason why Butler shouldn’t be enjoying the trappings of a solidly selling recording artist, not that he even cares about such things, but the vision of the amiable, dread-locked virtuoso musician in a clinically furnished hotel room seems nevertheless out of whack. Butler has just commenced the PR trail in support of his brand new album ‘Grand National’, a disc which still finds him very much the concerned world citizen, but musically this is his most positive and joyous release to date. Australian Musician’s Greg Phillips spoke to John about the new album the day after he’d played the Melbourne leg of the Big Day Out.

The man greeting us at the door of a swish modern suite in a flash Melbourne apartment block is John Butler. There’s something odd about the sight of Butler in this environment, in the same sense you’d ponder a man wearing a suit in the wilderness. There’s no reason why Butler shouldn’t be enjoying the trappings of a solidly selling recording artist, not that he even cares about such things, but the vision of the amiable, dread-locked virtuoso musician in a clinically furnished hotel room seems nevertheless out of whack. Butler has just commenced the PR trail in support of his brand new album ‘Grand National’, a disc which still finds him very much the concerned world citizen, but musically this is his most positive and joyous release to date. Australian Musician’s Greg Phillips spoke to John about the new album the day after he’d played the Melbourne leg of the Big Day Out.

GP: You’ve just played Melbourne Big Day Out, how was it?

JB: It was good. Melbourne’s a different kind of audience. You have to really remind yourself that they’re a little bit more … ‘in their head’. It’s nothing against Melbourne, it’s just that they’re a different crowd. It’s like they’re a little less primal, a little more intellectual. New York and Melbourne are very similar. They just get so much art, it’s almost as if the way they interpret it (the music), is like art. Then you get places …

I love places …where they’re really quite primal, like Sydney or Paris. It’s just different.

GP: Let’s talk about the new album. What ‘s the process when you bring a bunch of new songs to the other guys in the band, Shannon and Michael? Are the tunes pretty much in your head the way you want them, or do you allow the guys a bit of creative space too?

JB: I have an idea of how I want them. When I’m writing them on the night, or over the year or however long it takes to write the song, I definitely have a vision of what I want for the song, almost like a parent does for the child. You see potential and you want to point the song in a certain way and you have hopes for great things for it, like any child. But as is life, when you send your song out into the world or you send your song out to the band as well, you can only describe as much as you can and then you actually wanna see some spontaneity and you wanna see what the song can do by itself or what the musicians do to the song … without too much interference. Sometimes you can conceptualise a song too much and it can become too much of a cerebral activity and you want to it to be an instinctive, instinctual activity. So… that’s the fine line.

GP: You’ve got a new producer, Mario Caldato Jnr (Beck, Beastie Boys). What did he bring to the album?

JB: Well he co-produced the album with me, and he just brought perspective, sounds and a good vibe, and some good suggestions too. I had a very strong idea of what I wanted the songs on the album to sound like, but at times I lost perspective. I was a little too close to the canvas. Sometimes you just need somebody to stand back, or you just need somebody who’s just not that close to the work saying, “Be less precious”. My favourite parts of some albums are mistakes. Like the first G-Love album, he actually is clearing his throat in a song. He has, literally a lugie in his throat and he clears it and he keeps on singing it, and it’s just great. I love it. Sometimes you need someone else’s point of view, to see the beauty in a mistake.

GP: People will make up their own minds about the album, but how do you think it’s different to your other stuff?

JB: Uh, that’s a tough one. I don’t want to sound condescending, but they’re different songs! (laughs) Different players, it’s a different time and, uh, so… a different studio. There’s a lot of different things about it. If you want an emotive, spiritual foundation of where the songs are coming from, these songs are… a little bit more optimistic. Sometimes I wonder why I’m optimistic (laughs). I turn on the television, maybe it’s because I’m not watching much television, that’s what it is. I believe in love, you know. More and more I have to believe in love, ‘cause if I believe in anger and war and hatred, it’s only going to make more of it and I find the more energy I give those things, the more unhappy I am and more sick I am, more I feel like crap. So, it’s just more beneficial to me to be more concerned and focused on positivity and love, for my children, for my wife, for myself, for my music and for the people I surround myself with in the community I live in. Sometimes it’s just like a different take on the same things that keep on coming over time and time again, for human beings. I mean, most of the album is about the human condition and that’s what I’m more interested in writing about, the human condition. I was going to call the album “Love and War” because it’s either about love or it’s about war.

GP: Let’s talk about some tracks. ‘Caroline’ is quite an epic production, with some beautiful string arrangements. Did it take a while to get that one right?

JB: On the last album, with ‘Sunrise Over Sea’ and the song in particular I’m talking about is ‘What You Want’, it took about two, three weeks, if not more to arrange the strings with Shannon. It was our first time working together and we really kind of workshopped that one. And after working with each other for three or four years now… he obviously had a lot better understanding of my music. He does it all on MIDI so I can actually hear what it might sound like … and it sounded great. It was ninety-five percent there. Then he gets all the string players together. He transcribes it all, ‘cause he’s a freak (laughs) … and it was simple. So it was a real kind of moment when you realise that you’ve worked together with somebody long enough and you have an understanding creatively and personally that you can just … you start becoming like one organism.

GP: So what’s going to happen live with that one?

JB: What happens? Well, we either get string players in, which I’m interested in doing. So we could do that, or we do like what we do with ‘What You Want’, and bring different things out in my playing. We have a pretty big sound as a trio. We have a few tricks up our sleeves as far as to how to create… the best smoke and mirrors really. I’m not meaning playing with a backing track. I mean, just about how to play your instrument and make it sound like more. Using effects to your advantage. It’s interesting in a live situation, you know because aural distortion and compression, and the nature of reverb in rooms, it creates a lot of…you get like these hallucinations that happen, where you think you’re hearing more than what it is. What I really like is the distortion of the guitar and a cymbal crash together and they create this ‘shhhhhh’, like this harmonic sheet that becomes bigger than the parts by themselves, literally. It’s lovely hearing the distortion and cymbals together.

GP: Your music definitely has elements of the two main countries you’ve lived in. The country and the bluegrass elements of America and the space and the earthiness of Australia. The track ‘Nowhere Man”, did that come out of people asking you where you feel you belong?

JB: Yeah, pretty much. No one’s ever put the question that way. But, yeah, I get asked the question, it used to be daily but now it’s at least weekly. I’ve really thought about making a card that said, ‘I was born in America in 1975, I went to Australia in 1986. My father was American, my mother was Australian. We moved here. My Dad wanted to leave home, my Grandfather died in a bushfire in 1958’. Because people always think you’re going home wherever you are. I go back to America, and they think I’m going home. On the American front, it’s kinda that way, because I’m not home anymore, it’s not my home. It’s the place where I was born, and I have a connection to the place, but it’s not my home. It’s not, I’m not intrinsically linked to the land as I am here. But it’s strange being here, and people always wanting to know when you’re going home. You know, I am home… Here’s my card.

GP: Musically though, those elements are definitely there …

JB: Yeah, phew…it’s funny talking about Australian music, you know, because it’s such a young country, and comparing it to something like American music, which is such a… strange…and isolated beast of a place. I mean there’s no other place really where a country has influenced modern music so much. I mean, through colonisation, pioneers, slavery…uh, all these things that happened in the first 400 years of that place being colonised. I mean blues, jazz, country, bluegrass, I mean they all happened in the last 500 years. It just, it’s a freaky kind of thing to happen. Rock and roll, hip-hop. So you can’t compare that to Australia which is relatively young, and it only has to draw really strongly from Celtic and English song writing ballads and the Indigenous music, which hasn’t up until recent times, really connected. I think my music is highly influenced by probably American music and European traditions, you know, finger-picking and the nature of the acoustic instrument and the blues and rock and roll and hip-hop and reggae, but it’s all kind of Northern Hemisphere. I can put a didge in music sometimes and, I think it’s more of an outlook that the Australian point of view comes in. I think the interesting thing about Australia is its isolation. Apart from having amazing animals, the isolation in that gene pool, it also creates the same, on an intellectual and cultural foot. It creates a strange isolation and outlook on the world where you have… you can see the whole world, but you’re almost not fully connected to it. So it’s unique.

GP: Another track, ‘Gov Did Nothin’ which is about the lack of response by the Bush administration to Hurricane Katrina. I’m interested in the incidentals. The water sound at the beginning, how did you record that?

JB: (laughs) Ah, with a bucket. It just seemed like a good idea at the time. That song was finished pretty much before we went into the studio, and two really distinct things happened. One, that I got really sick of hearing the lyrics and the melody. The melody that I was singing, I thought I had done a thousand times before, and I was just kind of unimpressed with my effort. The second thing was Mario suggested maybe a drum jam. He mentioned a Rolling Stones tune where they have some kind of Latin feel at the start of the song … so that thing at the start of the song somehow also found itself in the middle of the song and basically set the whole scene. Then somewhere along the line I started hearing rain and thunder and helicopters (laughs) and water. We had to kind of mask the water sounds with rain and thunder and helicopter, ‘cause just by itself, it was all this percussion and water, like a drum jam and a bathtub…it a bit lame!

GP: And the Bull sisters’ vocal at the end? Is that improvised?

JB: Well, the backups for “Gov Did Nothin’” weren’t. We had a good idea of what we wanted there, and Michael suggested those guys come in. But in the middle, the solo, Vika just went off! We suggested to her to do this kind of chordal thing, just to slowly build up as the improvisation goes to this kind of climax, and she went in there and did this like … Floyd, ‘Gig in the Sky’ kind of vibe, and we thought … “This is amazing!” She just kinda let it out. That was probably the most strongest moment, as far as somebody from outside the band coming in and really putting their soul on the line. I think when you totally wail, you just let everybody into the deepest, darkest, most beautiful, yet ugly sides of you as well, and she did that to a tee.

GP: Just a bit about the gear, which has been pretty well documented in this mag and others, but did you use anything new on this one? Changed pickups or tweaked amps or anything?

JB: I used to go through Sunrise Magnetic pickups and now I’m going through Seymour Duncan. Mag mics, but I don’t use the microphone, I just use the magnetic part. My onboard is really starting to change. I go through a couple of Avalons and a Midas for my Blender now. It’s like a really fancy Blender compared to the ones I had before. But that’s not a really big part of this album’s sound, but it is part of it. It’s like two mics, a D.I. and a clean amp and a dirty Marshall and that’s all happening at once. It has one sound, you know?

GP: You only string your twelve string guitar with eleven strings. You haven’t put the high G string back on your Maton ECW80C to see what you disliked about it?

JB: No, no I haven’t. I haven’t forgotten what I dislike about it yet. I’ve been told I should go with two wound G strings, so maybe that’s something I should figure out at some stage.

GP: So, what can you tell me about the new Maton?

JB: It’s a Messiah, custom-made one, and she just needs to be beaten in. My main guitar is ten years old and it’s been very well used, and it’s only just starting to sound really good over the last three years. Like all guitars, and especially twelve strings, you really need to… for want of a better word … beat them in. I know it sounds terrible, but you have to really get out there and kind of use it a lot and not be too precious and really get that wood supple. Let it know that you’re going to be around for a while.

GP: What about the recording of the guitars?

JB: Just two Neumanns, a stereo this time round. A stereo, and a mono. Other times I just go a Neumann and a directional. And that’s usually the sound for the acoustic… and it goes to the pre-amps as well. A lot of pre-amps offer an almost artificial bottom end that you can’t get from a mic. So, you can roll off all the tops, but you can get a real punch to it that you can add the the microphones.

GP: At the ARIAs Rob Hirst suggested that not enough artists were using their music to say something, and he singled you out as doing it on your own. Does it bother you that other artists don’t speak up more?

JB: Well, I’m of the opinion, as a footnote to this question or answer, that he was generalising. As you do in most public situations, generalise it … otherwise you’ll be there for the next two hours to discuss the intricacies of an issue. So he was generalising about commercial mainstream music … and there isn’t! It’s quite a bleak scene as far as opinion is concerned. I mean, worldwide, there was Rage Against the Machine for a while, and there was U2 and then on the Australian scene there’s Powderfinger and Living End, you know, on the commercial scene. But the minute you go underneath the mainstream it’s rife. It’s everywhere. It always has been and it always will be. So, you know he was talking very specifically, and generally about mainstream music, which is this kind of, lately been very homogenised by lots of different factors, whether they be media or radio DJ programmers that take zero risk. But as far as the music scene is concerned, man, there’s people talking about stuff all the time. It’s the nature of music, you know, that a large portion of it is going to be about what’s going on in society around us. That’s just art. Especially folk music. So I don’t feel alone. But I agree with Rob so far as to say that there’s not a lot of it in mainstream music. If you look at some forms of art and media … you’d never know there was a war going on. I don’t think all music and art has to do that. Some music and art just has to be about shaking your butt and really escaping and having a good time. I really think that, in some way or another, really adds to the love in the world. Just to celebrate life!

GP: You’ve really put your money where your mouth is in regard to helping up and comers in music with the JB Seed Grants, you must be happy with the way the grant has progressed?

JB: It’s in it’s third year and it’s doing really, really well. We really feel, in a strange way, proud to be a part of it! It’s an honour to be one little step along a very long road for musicians…. not even push you along or prop you up, but just one little helping hand. It’s a real honour to be part of that. That was part of the dream, was just to help people along the way, and hopefully they become self-sufficient. No matter what avenue they go down, whether that’s independent record deal, becoming an art teacher, whatever that may be, just that you can pay the rent and feed yourself and do what you love to do. That’s what I’d like to help people to do, because that’s the definition of success.

GP: I know music is what you do for a living, but what does music … pure and simple music mean to you?

JB: I saw a bit of graffiti in New York that said, “Music changes people and people change the world” and I really think music can do that. I think music has been there a lot for me, you know, whether it be Tracy Chapman or Rage Against the Machine or Midnight Oil or you know, a thousand and one artists that have really touched me. I think that’s an amazing power that music has. I think the gift of sound and the gift of words together is an extremely potent medium. So potent that, you know, advertising campaigns, political campaigns … we use it to sell people stuff. We use it to convince people of stuff. I really believe when things are really happening right on stage, and we’re really connecting with the audience, and the audience is…and when the barrier between the audience and the band really dissolves and we become this warm thing that kind of is…I dunno … you just become bigger. It’s bigger than all the parts separate. We come together as a band and an audience and it’s just harmony. You really feel like anything’s possible. That’s what I love about music, it makes me feel that anything’s possible.

For information on the JB Seed grants, visit www.jbseed.com