November 29, 2007 | Author: Claire Hedger

Long before Missy Higgins, Adalita, Clare Bowditch and co, there were other equally as talented female artists, that to this day haven’t had the kudos they deserve. Claire Hedger salutes our seminal female rockers.

The majestic Regatta Hotel is an historic pub in the Brisbane suburb of Toowong, facing the Brisbane River. Though now converted into trendy modern bars and nightclubs, the hotel’s history is enshrined by the Australian Heritage List and the National Trust of Queensland. Dating back to the first appearance of a watering hole on the site in 1874, the building is an existing snapshot of our architectural history.

And yet, for Australian women, and indeed, for Australian musicians, the Regatta Hotel represents more than just a preserved antique structure. It is a site that captures our social, political and cultural history, and where, on a hot Summer’s day in 1965, the path of women’s fight for equality, and where subsequently – though maybe less obviously – the course of Australian music was changed forever…

Telling the history of Australian female musicians is a tricky mission. Women are – and always have been – musically innovative in Australia, often at the forefront of new musical formats. Indeed, today, it may not seem necessary to hold a distinct celebration for Australian female artists for they pervade all musical styles and levels of performance. The danger, therefore, is in providing a separate women’s history that’s not integrated into the fabric and context of our country’s musical heritage. In truth, however, mainstream accounts have often relegated women to mere decorative pieces in the margins of our music history, burying them amidst stories of heroic men and their sexual exploits. So we wonder, contrary to the portrayal of women in one particular historical document, whether Helen Carter, bass player with Do Re Mi, was more than just ‘one of Bon Scott’s last girlfriends’; if Jenny Morris was not just ‘a flatmate to Michael Hutchence’ and how Vika and Linda Bull may have exceeded way beyond just being Joe Camilleri’s backup singers.

There’s no rule to say women should only take inspiration from other women, but without knowledge of our musical forebears, we have no choice. Any curiosity we might have about the great female musicians of yesteryear goes unsated. So while we’re familiar with the adventures of Billy Thorpe, Brian Cadd, Lobby Lloyde and other male greats of Australian rock’n’roll, we know less about Allison MacCallum, Bobbi Marchini, Jeannie Lewis, Sharon Sims or Kerry Biddell.

The rationale in resurrecting the stories of Australian women in rock is logical. Songwriter, Joanna Piggott, of late-70s rock band, XL Capris, might have gained comfort from knowing women before her had picked up the bass guitar, ignoring the then-unspoken gender rules of rock. “I remember in high school, up the road, there was a band playing and practising in their garage”, she says. “And just thinking, I would never be able to be in this world ‘cause I’m just not that kind of girl’”.

There are, of course, moves to rectify the omission of women from the annals of rock. As Renee Geyer explains: “In 1985 there was a book published about Australian rock’n’roll from the early 70s through to the present, compiled by Ed St John for Mushroom Records. Everyone who even made a burp on a record was in there, but they completely left me out. There was not even a mention of my name. It was as if I’d never existed! I was in shock. I ran into Ed St John somewhere and asked him why I wasn’t in that book. He said it was probably because I didn’t have any records out at the time. Also, he thought that I was getting out of the rock’n’roll business and moving into cabaret. Huh…? … I was amazed that my whole past had been erased. I don’t think it was malicious; that’s the sad part. They just plain forgot about me.” [blockquote]“I remember in high school, up the road, there was a band playing and practising in their garage”, she says. “And just thinking, I would never be able to be in this world ‘cause I’m just not that kind of girl’”.[/blockquote]

So Renee wrote her own story, and now we have a growing library of autobiographies from a diverse array of artists from Chrissy Amphlett to Helen Reddy. These women, tired of being ignored or misrepresented, have resorted to writing their own stories, giving us privileged access to their own point of view. Renee, of course, is a key influence in many women’s lives. “I think what’s great about Renee is that she’s a genre to herself,” says Angie Hart. “She’s definitely ridden the wave and it’s something to be strived towards”. Paying tribute to the Australian women of rock, not only resurrects women’s roles in history but gives us some sense of where we have come from.

In the early 1960s, television was the main medium for female performers. Two-thirds of all Australians had a tv in the home, and the small screen presentation of rock and pop culture, which at the time was still suffering a reputation as a threat to the moral fibre of a nation, meant it could be carefully monitored. So when women like Betty McQaude, Lana Cantrell and Noeleen Batley made the transition from clubs to tv, their image was manipulated to represent something more conservatively feminine. Judy Stone – self-described as a cross between Dusty Springfield, Petula Clarke and Vera Lynn – started out as a country and western guitarist and singer, touring country towns with Reg Lindsay. When she joined the Bandstand family at Col Joye’s invitation, he encouraged her to drop the guitar and “just sing and be pretty”. Judy Cannon, influenced by Johnnie Ray and Elvis Presley, was originally a rock singer who worked with the Thunderbirds from 1959-61. Betty McQaude, whose vocal workouts were influenced by the raucous blues singer Wanda Jackson, had also performed with the Thunderbirds. Both women, however, forefeited their rock’n’roll style to be relegated a more ‘comely’ and amenable position on tv. As Patricia Amphlett, (or Little Patti, as she was then known), explains “it was always the male who, no matter how unknown he might be, or how known I had become, the blokes got the top billing.”

“The girls were pretty fill in between the male acts, wore pretty dresses, sang cute songs”, says New Zealand born, Dinah Lee, one of the few to subvert the trends with the mere force of her presence. “I was lucky. I had this image that created something a bit more powerful. When I sang, it wasn’t cute and pretty. I belted out songs. It took me from the pretty singer to being the star, where all of a sudden, I could do my own tours with men listed on the bill under me.” While women on television were battling the pressure of restraint and restriction, another battle was taking place in the untamed wilds of the local pub. A battle that would set in motion a chain of events that would eventually, and unexpectedly, forge Australia’s unique pub-rock sound.

In 1965, two women, Merle Thornton (mother of Sigrid) and Rosalie Bogner, walked into the public bar of the Regatta Hotel, calmly took out a dog chain and padlock, chained themselves to the bar rail, and asked for a beer. In the early 1960s, the public bars of Australian hotels were an exclusively white male domain. Women were expected to either wait in the Ladies Lounge, or sit patiently in the car while their husbands brought them refreshment. Fed up with this gender-segregation, Merle and Ro decided their waiting was over. Polite protest was no longer working – aggressive and disruptive action was needed. Feminism, they thought, could no longer sit in the hands of the ‘hat and glove brigade’. So they stormed the male bastion of what has since been been dubbed the ‘ocker keg-culture’.

When news of their actions hit the headlines, all hell broke loose – women in a hotel?! They sparked outrage around a country panicked that the “women’s desire to drink was a sign of impending licentiousness and moral chaos”. When the police arrested them, the first question Merle and Ro was asked was, “where are your children and why aren’t you at home looking after them?” How dare they shrug off their duties as mothers and wives! But, in a turbulent climate of changing social, cultural and political attitudes, many women who heard the news were on their side. In an act that has been historically captured by the ABC’s Four Corners program, they led a pub crawl of dozens of women through the city’s hotels, each carrying a bottle of beer in their handbags in case they were refused service. But it was not just the right to drink in bars they were seeking. As Merle Thornton claimed, “we are after equal education opportunities for women, equal job opportunities and equal treatment in every direction.”

This seemingly simple act would change the structure of Australian urbanity, and, consequently, the direction of live music in Australia. It meant the liberation of pubs and the opening up of that once-exclusive space to a new kind of clientele. Just as the pubs were easing their codes of gender-segregation, large venues, such as town halls, were closing their doors to live music. There was a critical need for musicians to find new spaces to perform. By the end of 1970, liquor laws had changed and hoteliers had found a new way to bring younger patrons through their doors – with live music.

As the pub circuit took over from the old dance circuit, and now fuelled by alcohol and the rapid development of PA systems, it brought a different attitude and a harder-edged music from the likes of the Aztecs, Madder Lake, Captain Matchbox, Spectrum and Chain. With their entree to the public bar, female musicians likewise found a new space to perform beyond the restrictions of variety television and proved they were as capable as the men to rock.

In the late 60s and 70s, the international counter-culture was creeping across Australian borders, bringing with it new ideals about sex and love, about peace, spirit and meaning and about alternative lifestyles. It was the era of Richard Neville’s Oz Magazine, of the Yellow House and Pram Factory artistic centres, of Moonies, Hare Krishnas, hallucinogenic drugs and the avant garde theatre, film and art movement. Women were vocally and forcefully fighting for equal rights and opportunities, and for autonomy over their own bodies. All this helped to bring an appreciative audience for the once-ignored Australian female voice.

Margret Roadknight was one of the first women to brave the pub circuit, taking on Bob Hudson’s social commentary, ‘Girls in Our Town’. With constant touring and radio airplay, she made a hit of the lyrical lament of liberal teenage sexuality, shifting the boundaries of what women could or should sing about in our once-conservative nation. A performer of blues, jazz, gospel, folk and comedy across the world, Margret is a living musical treasure, and yet it takes overseas visitors to remind us of her legacy. As American author Dr Maya Angelou said at last year’s Sydney writer’s Festival, “You have a blues singer in Australia – Margret Roadknight – listen to her!”

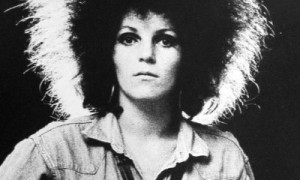

[blockquote]In 1965, two women, Merle Thornton (mother of Sigrid) and Rosalie Bogner, walked into the public bar of the Regatta Hotel, calmly took out a dog chain and padlock, chained themselves to the bar rail, and asked for a beer.[/blockquote] Part of the international community, Australia couldn’t help but be influenced by musical trends from overseas, and in the 70s we adopted the sound of American roots music. “In the clubs, they played lots of obscure kind of Motowny sort of things that you never heard on the radio or anything,” says blues howler, Wendy Saddington. “So you heard a lot of black music in Sydney”.

Wendy is considered a pioneer of the pub rock scene of the 70s. She first started singing Bessie Smith songs at a place called the Love Inn, in Carlton, then Bertie’s, Sebastian’s, the Garrison, the TF Much Ballroom, Ceasar’s Palace and the Thumpin Tum. “There were three jobs a night sometimes in those days,” says Wendy. Her mother introduced her to the greats like Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Bessie Smith and Miriam Makeba and she blew audiences away with the sheer force of her voice, as captured in performance by Peter Weir in his 1970 short rock music film ‘Three Directions in Australian Pop’. Holding her own with prog-rock bands like Chain and Copperwine, she became one of our most popular and prominent performers of the era. “When you’ve got a good band behind you, you’re only as good as the band really, they’re pushing you and you can ride the rhythm. The music clicks. That feels good. And if the band’s not so good, you’re sort of pulling the band, or dragging the band.”

Another woman to brave the male-dominated pub circuit was Renee Geyer. Renee considers her album It’s a Man’s World a “landmark” in Australian female vocal recordings because “it was the first time (with the exception of Wendy Saddington) that an Australian woman really ‘tore up the mike’ with completely uninhibited vocals and adventurous, almost masculine phrasing.”

Renee and Wendy were not alone on the pub circuit. Described as a “pint-sized fiery red-head” and compared to Tina Turner and Janis Joplin, Allison MacCallum “bolted out of the blocks screaming her straight up hard rock and howling blues”. Though she started out singing jazz, blues and Motown material, Go Set described her as “one of the few girl-singers who concentrates on singing rock songs rather than blues or ballads”. One critic reviewed her song ‘Any way you want me’, by writing “she moves from a smokey lower register at the start then lifting the song a full octave to showcase her beautiful howl.”

When she arrived in 1967 amongst the female solo singers like Judy Stone, Allison Durbin and Little Pattie, she wasn’t going to don the pretty long gowns that the other women wore. Though she recorded and performed with Freshwater, Tully and One Ton Gypsy in the early seventies, she mostly did it solo rather than as part of a band.

In ’72, Allison had a hit with Vanda and Young’s penned ‘Superman’, which was resurrected in 1979 with the release of the Christopher Reeve film of the comic hero. As part of the Alberts label, she recorded with 2 of Australia’s finest vocalists – Bobbi Marchini and Janice Slater – under the moniker of the Hooter Sisters on a 3-way vocal workout of Phil Spector’s ‘To Know Him is to Love Him’. Though she may be remembered for singing the ALP election campaign theme song, ‘It’s time’ (which helped Labor win government for the first time in 23 years) she did in fact have the first album by an Australian female artist to make the charts. As previously written, “Allison broke quite a few rules for women, set several precedents and enjoyed success on her own terms. Above all, there was that joyous, howling, shrieking, gutsy, reckless, warm voice.”

Allison crossed paths with other stalwart women touring the pubs. There was Sharon Sims of the band Flake, Marcie Jones of Marcie and the Cookies (who “sang with a lot of grunt” in the motown soul style), and UK-born, Linda George. Linda’s soulful voice on her 1974 hit ‘Mama’s Little Girl’ was counterpointed when she played the Tina Turner’s role as the Acid Queen in the Australian production of The Who’s Tommy.

Kerrie Biddell, with her “beautifully clear-pitched voice with its endless range”, was a winner of the Battle of the Sounds in 1970 with her band, The Affaire. It took her to England, then later, America, where she became a regular on the Midnight Special tv show, singing with the likes of Blood, Sweat and Tears, the Hollies and Billy Preston. She also found herself as part of Dusty Springfield’s backing group. “A friend said he was looking for girl singers who could read music,” she explains. “He needed three to back up Dusty Springfield at Chequers. I thought, Oh, I can’t do that! But he said I had to do it for him. So I did it. I had to read these charts with awful pencil cross-outs all over them – and in the dark! At the end of the 3 weeks I lost my voice.”

Jazz performer, Jeannie Lewis, worked the folk circuit before spanning over into the singer/songwriter field in the 60s and 70s. Her work crossed many musical boundaries, and she toured the circuit constantly, building up a loyal audience. Like Allison MacCallum, she also sang with the band Tully and in 1974, she won the Best Australian Album title, despite next to no airplay. Touring the pubs was sometimes the only way for these women to create and audience. Getting airplay was actually quite difficult in a musical climate that viewed women as a genre. As Helen Reddy once said, “I would be told things by radio station managers like, we can’t play your record, dear, we’re already playing a female record”. But the pub-circuit also wasn’t particularly kind to women who were trying to stake a claim in the heart of male territory. Those who ventured in were brave souls indeed. As one observer noted, “almost every aspect was geared towards men; the male look, the male voice and the male point of view.”

“I think I was getting a bit burnt out by that time, a bit tired of it all,” says Wendy Saddington. “The late nights and the lifestyle. You get sick of it, you know. You’re always in a pub, and you’re always around a certain kind of people, and you – I felt that I was kind of losing myself, because I was very young when I started. I sought protection, I felt kind of not safe in that world. Because it’s alcohol, drugs, and a lot of people have died. Or a lot of people have lost their minds. Or a lot of people don’t know who they are. You get fried. It’s a hard life that night life.”

“Being in a band taught me a lot of things a girl wouldn’t normally learn”, Alison MacCallum said in a 1972 interview. “I found out, for instance, that there are more liars around than I ever would have imagined. I saw the lies handed out to chicks by guys from bands and it opened my eyes a lot”. She added, “There aren’t many girl singers with bands because they aren’t encouraged and tend to drop out after a while”.

By the late 70s and early 80s, the musical climate was shifting again, first towards punk and then to English new-wave. Like Merle and Rosalie in 1965, these two musical styles freed women to occupy once male-dominated spaces. “I think I was very lucky because I could have been surrounded by people who said, ‘look you’re a girl don’t worry’,” says Helen Carter, bass player with Do Re Mi. “But with punk, I did have a lot of particularly English role models I could look to, say the Slits, the Modettes and the Aupair’s.”

But punk has been described as the “great leveller”, with “the kind of punk ethic where anyone would get up and have a go”, as Helen puts it, and it encouraged women to take to the stage, and to instruments. “We’d only just got access to bars in the seventies, we weren’t even allowed to drink in bars until the seventies”, says drummer, activist and Queenslander, Lindy Morrison. “And it was in Queensland that people like Meryl Thornton chained herself to the bar so all that was really in our minds… music in the seventies in Australia for a women was pretty bloody terrible, the pub culture. …the kind of culture of music in the seventies was really a male culture and we had the Sports and we had the Angels, Cold Chisel and for someone like me it was very difficult …for me to identify. Punk allowed women access to the stage.”

Others also found the new musical styles more suited to them. “Right at that time was when all the music from England and America was coming in… New Wave and Punk – and strange women doing stuff like Patti Smith”, says Joanna Piggott. “Just stuff that really appealed but also blew apart the idea of what rock music was. it was just at that time when it was really ok to just go and pick up a guitar and start playing three chord thrash songs and writing stuff over the top that was completely non-melodic and non-rock, and there was an audience who wanted to hear it.”

She continues, “I have always thought that it was the opening up for weird women, like weirdos like me, who could just come in and be completely fine, feel quite at home. Whereas before that, if you didn’t sort of look good or sing with a great voice… It always really pissed me off that you had guys with weird voices making records and singing, but girls always had to have the real big good voice. And I reckon at that time, for me, it really opened the doors to strange women.”

Jane Clifton, of Sydney seventies punk band, stiletto, who were described as “radical and intelligent rather than glamorous and sexy”, reflects, “It was a milestone, a milestone in Rock’n’Roll! It was also a journalists’ picnic and did we have stories to tell them! We told them about the bad old days, but we also told them about the brave new age that was to come, when girls would inherit the Rock’n’Roll scene and play all the lead guitar licks with Van Halen.”

Postpunk and new wave broke down the pomposity of masculine rock music and women realised there was nothing stopping them from playing either.

Margot Moir, of sweet-harmonied sibling act, the Moir Sisters agrees. “It was a time for women to sort of start doing something, to break free. I think we just got caught up in it as well, and thought, ‘Oh well if these women can do it, what’s stopping us?’” It was a combination of the spontaneity of the new musical style and the inspiration of women who had come beforehand that influenced one of Australia’s most impressive performers of all time – Chrissy Amphlett. She says , “The earliest thing I saw was Wendy Saddington – she really inspired me to be a rock and roll singer. I loved her. And she was a little crazy and she was wild. Someone like Renee Geyer always had a scrappy attitude. You know, those sort of girls, I admired.” She continues, “Then when I saw Deborah Harry in a bathing suit and I thought “Ah, that’s it”.

Inspired by her cousin, Little Pattie, Chrissy Amphlett decided music was her business too. “I saw my cousin on the TV and even though I really didn’t know her… It was just everything was possible, it was possible because she was on there, singing.” The Divinyls formed in 1980 and within a year, had their first hit with ‘Boys in Town’. It was their enigmatic lead singer and songwriter that made the group stand out from the pack and she certainly wasn’t going to be your typical demure ‘showbiz type’. “I was going to break a lot of those things down and i wasn’t very popular [for it]”, says Chrissy. “I wasn’t going to play it the way you were supposed to do it here [in Australia]. I didn’t want to be this phoney showbiz person so i went the other way and was as horrible as i possibly could be… because i felt all the girls up til then had to be this nice girl”.

“I remember being, as a kid, like shit-scared of Chrissy Amphlet because she was renowned for doing some pretty radical stuff live,” says Kate Ceberano. “Like she would get a mic stand and if any young lusty men got a bit fresh, she’d whack ‘em in the head! And I heard she was urinating on stage and I was freaking out, thinking maybe she’s going to take umbrage to me. But she actually was really sweet and she was really supportive.”

Chrissy’s post punk approach did more to subvert stereotypes of female performance than years of prudish calls for censorship. Long before Madonna deconstructed the male gaze with her display of exaggerated sexual cabaret, Chrissy showed that women no longer had to be tame and predictable to be successful. She shifted the ground rules and inspired many women to do the same. “The school uniform was very handy for me because I didn’t have to think of what I was going wear and I could easily wash it and hang it in the bathroom at night”, says Chrissy. “I was building up this persona which was a good defence mechanism for me to ward off all these people and men were quite scared of me and I liked that. I was quite aggressive.”

“Chrissy Amphlett would have to be my favourite Australian female artist because I think that she is a provocateur of the highest kind,” gushes Kate Ceberano. “She’s willing to take risks and she’s bloody great at what she does… I reckon she’s the Judy Davis of rock-n-roll.” As the amps got louder and the competition to be heard got fiercer, women’s voices necessarily became more assertive and forceful, changing the sound of Australian rock. “The vocal style was created by having to shout above extremely loud, loud, loud, turned-up-to-eleven marshall amps,” Says Joanna Piggott, “so there wasn’t a vocal style at all. All it was, was screaming over the top of noise… and, then we had to make a record out of that. It was probably the only time that a girl with a voice like a rat actually couldn’t get to make a record up till that time.”

“It was always very competitive on stage to be heard and so that’s how our music developed,” notes Chrissy. “You’re in a very smoky, beery loud environment, sweaty, hot. That all helped to develop the sound and the music.” She continues: “in those days you would be put with a big band like The Angels or Cold Chisel. Inxs and Divinyls were the ‘baby bands’. We would go out and tour with the bigger bands and that’s how [we developed] that aggressive sound – from being with the bigger bands.”

Punk may have encouraged more women to take to the stage, but it didn’t resolve some of the more fundamental problems, with old attitudes about female performers seeming harder to erase. Chrissy Amphlett observes the attitude when she explains how “John Enwhistle from The Who said, ‘Christine, you’re a pretty girl, why don’t you just stand there and sing?’ So I probably nearly punched him.”

It was even problematic for women who eschewed the microphone and picked up instruments instead. When keyboardist Sharon O’Neill arrived in Australia, she remembers “a record company executive from America coming out and seeing a show and telling my record company, ‘here, she’s got to get out from behind those keyboards. She’s got to be up front. We’ve got to see her.” She turned the tables on them, though, when her song, ‘Maxine’, about the toils of a woman on the streets dealing with the gritty and real situation of drugs and prostitution, became her biggest hit.

Attitudes towards female instrumentalist continued to pervade the scene. “We played around a couple of the pubs and I never felt like a novelty, but I certainly had difficulties with people not believing i was in the band,” remembers Helen Carter. “There was always some reason for me being in that position other being a good bass player. Later down the track there’s all those stories of bouncers at the door saying ‘Oh you’re carrying your boyfriends guitar’ and ‘can you prove you’re in the band’”.

“You get these men, ‘saying sit on my face!’,” continues Helen. “And Deb and I would go, ‘Why? Is your nose bigger than your dick?’”. Their ‘take no shit’ attitude would inspire the band to write a protest of male chauvinism with their song, ‘Man Overboard’, which snuck under the radar and onto the airwaves. “People used to make a fuss that it had penis envy, pubic hair and anal humour in the lyric”, says Deborah Conway. “But, actually, the most scandalous thing about it was that it didn’t have a chorus.”

Women on drums have likewise struggled to prove their legitimacy as musicians. When Kathy Green first auditioned as drummer with X, preconceptions of what women could do musically meant the band had a standby in the wings in case she faltered. “We were playing at the club and there’s a call for Ian [Rilen],” says Kathy. “And, apparently, it was Doug Falconer lined up around the corner with his drums in the car, because Ian didn’t think I could cut it. It was, ‘the little girl’s cute but she can’t really cut it’, until we got playing so then it was just on from there.”

And yet, female drummers have provided some of Australia’s most exquisite musical moments, such as Clare Moore with Moodists and the Coral Snakes, and Lindy Morrison with the Go Betweens. When Lindy was told by Helen Razer and Judith Lucy on their JJJ program that seeing her play drums when they were 17 had completely changed their lives, she says it was a completely satisfying moment. “I always played for girls. That’s all I’ve ever been interested in – the stream of women’s culture”.

“In the early eighties there was a gig everywhere or every bar was a gig,” says Deborah Conway. “And there was a band just about anywhere you could walk into – the pokies still hadn’t started to rear up in Victoria. Live music was supremo in Melbourne at that time. There were some women around. Countdown was full of women, but I guess there wasn’t that many in the local scene. They were not as thick on the ground as they are now.” With so few women apparent on the ground, the tired old attitude of lumping women together as a genre continued to pervade. “There was a bill, where we were supporting Wendy Stapleton and The Divinyls”, says Kate Ceberano of her time with I’m Talking. “And this was like the three ‘women in rock’ at that time, playing down at the venue, the old venue in St Kilda, which doesn’t exist anymore. And I remember it was a big brou-ha that there was three women to the bill and I kind of didn’t get the feeling like you were sisters in rock or anything.”

Touring has long had its pitfalls for women in Australian rock, yet many have managed to challenge the male space of being ‘on the road’ and made it their own. “I remember touring with Simple Minds and Icehouse and I was the only girl on the tour,” says Chrissy Amphlett. “And I remember just trying to find a spot on the bus where I could be alone and all the roadies would stand over me and I’d be asleep and wake up and there’d be all these roadies standing over me, staring at me and teasing me … you had to sink or swim, you had to stand up for yourself, so I suppose I built up this shell around me and this persona and it was good, it was quite scary, but I wasn’t really like that underneath. I had to build this person who would survive in all this. So people were a bit afraid of me and they wouldn’t come near me and it worked.”

“We went to every town in Australia – we toured like you couldn’t even imagine”, says Angie Hart, remembering her days with Frente! In the early 90s. “I remember being in this mining town in Gove and this guy standing up the front of the entire show with his penis out of his pants screaming out for me to ‘F- off’ – then coming up to me at the end of the show saying ‘I’m really sorry about that, it’s just my way of saying that I like you and can I get an autograph for my sister’. That kind of encompasses everything about touring Australia – what it was like for me at that time.”

So have the cultural prejudices against women touring or playing non-traditional instruments been successfully challenged out of existence? Janet English of Spiderbait, Stephanie Bourke of Something For Kate or Kellie Lloyd of Screamfeeder may provide answers elsewhere on whether they’ve encountered similar problems as they’ve fronted up to the band room with their bass guitar. In 2007, one would hope not.

[blockquote]“And I remember just trying to find a spot on the bus where I could be alone and all the roadies would stand over me and I’d be asleep and wake up and there’d be all these roadies standing over me, staring at me and teasing me … you had to sink or swim, you had to stand up for yourself, so I suppose I built up this shell around me and this persona and it was good, it was quite scary, but I wasn’t really like that underneath. I had to build this person who would survive in all this. So people were a bit afraid of me and they wouldn’t come near me and it worked.”[/blockquote] It is Janet, Stephanie and Kellie’s generation that have played a major role in the maturing of Australian rock music, as women in 90s rock played a major role in the crossover between the indie and commercial charts. Women brought an exciting sound out of the margins and into the mainstream. As Craig Mathieson illustrates in his book, The Sell In, “the nineties were a time when female vocals were in favour in that nebulous space that sits between the independent and mainstream musical spheres, particularly with the crossover popularity of bands such as the Hummingbirds, the Clouds, the Honeys, the Falling Joys and Def FX”.

Indeed, Alannah Russack and Robyn St Clair of the Hummingbirds flew in the face of their record company’s attempts to turn the girls in the band into glamour queens – Robyn shaved her head just before an important photo shoot. She said “Pretty girls and pretty boys in bands was their marketing angle, but now we weren’t pretty because i was ugly”. They acted as role models for the Clouds, who found themselves up against a similar attitude towards women in rock. Jodi Phillis and Tricia Young of the Clouds were told “why can’t you write songs that have great girlie vocals, harmonies and the rock thing?” Instead, they recorded songs about childbearing, motherhood, incest and, with ‘The Sweetest Thing’, critiqued the male posturing of hard rock.

Their approach inspired Suze de Marchi of the Baby Animals to return from London when she saw the great things happening back here for women. “The people at the record company didn’t know what to do with me, they just wanted to me to go with Stock Aitken and Waterman and do that sort of pop thing, and I totally baulked at that and just thought, I knew so many more musicians back in Australia, and I thought the scene here was so healthy. That’s when I decided that get back home and get a band together and get serious about it.”

Having followed the cues of women before them, 90s female artists saw it was possible to subvert the machinery’s attempts to contain them. Issues around female sexuality became a whole new ball game. Adalita of Magic Dirt wrote of child abuse in her music and other women, like Rebecca Barnard, Jenny Morris, Robyn St Clair and Deborah Conway, broke taboos and brought the reality of sex and rock to the stage by performing while pregnant. No one would dare ask these women ‘where are your children and why aren’t you at home looking after them’, as had been asked of two women in a pub four decades before. As Deborah explains, it shone a whole new light on women’s sex and sexuality; “I was about five six months pregnant with my second child and I got this dress designed that was completely covered in red sequence apart from this big cut out golden heart in gold mesh with diamantes around the edges. It just went straight over the belly. Which was beautiful and it sort of was cheeky and it was drag and it was sex. I was really pleased with that because it was kind of like, a) yes I’ve had sex, and b) I’m here to tell you all about it, and c) there’s a kind of grubby other reality here as well that’s not just tight tiny tight pert littleness, there’s a kind of big sprawling womanly force about sex that’s empowering as well.”

While there’s not enough room here to tell the stories of all the influential female musicians in Australian rock history, it is timely to remember that women have always played an essential role in the narrative. We can see just from these few stories how important it has been for women to be aware of their forebears in rock, as each generation has built on the efforts of the one before. Women have shown great musical versatility in their ability to straddle rock and pop, punk and new-wave, stage musicals and comedy, jazz, blues, soul and folk. A sneak peek can at least encourage all to be curious about the obscured artists of yesteryear as we know that it is just the surface that has been skimmed. By paying tribute, we can remember and celebrate those who shifted the boundaries before us, rather than take for granted the position we’re in now. Maybe soon, an integrated history of our musical heritage will bring women out of the sidelines and into their rightful place in the heart of Australian rock history, no longer to be considered a genre on the margin. As Kurt Cobain once said “the future of rock belongs to women”. We also know that the history does too.

***Claire Hedger has contributed to the Australian music industry for 20 years. She is currently editing her PhD thesis, which explores the experiences of women in the rock and pop industry and how women have challenged the boundaries that have traditionally constricted their performance. Some of the quotes in this article came from research during ABC-TV’s music docos, Long Way to the Top and Love is In the Air, for which Claire was a writer, researcher and interviewer.